Plunge in DOD contracts incentivizes more war, jeopardizes Greensville County

The manufacture and sale of “transparent armor” to the Department of Defense to protect personnel operating military vehicles has long been a mature industry in the United States. When the Department of Defense issued a series of U.S. Army contracts for windows to be installed in “mine-resistant ambush-protected” all-terrain vehicles known as “MRAPs” in 2014, it wasn’t seeking cutting-edge, technological advances. Rather, it wanted competent contractors to bid (through “source approval requests”, or SARS) on making transparent armor according to a government-developed and owned “secret recipe.” This item was so routinely procured, inventoried and installed that it even had its own “stock number.”

For the newly opened Israeli subsidiary Oran Safety Glass in Greensville County, there were only two major challenges it would face if it won competitive bidding for the contracts. The first was that the US government owned not only the “recipe” but also specifications about the threats against which the glass would protect as well as the ballistic testing procedures for the glass. This is US government classified information at the SECRET level. Oran Safety Glass in 2014 did not have an officially designated “facility clearance” for handling such classified information. It also had no way to efficiently procure the materials needed to produce transparent armor to the specifications in the government’s “secret recipe.” Neither of those obstacles prevented OSG from bidding on and lowballing US industry leaders. OSG won five contracts between October 2014 and 2015.

In 2015, one of those US industry leaders, Schott Government Services, contacted the Army and requested production control ballistics testing of OSG’s shipments. The Army soon discovered that most of the OSG manufactured armor was “out of specification.” Alarmed, the Army formally notified OSG that such products manufactured by means other than its own “recipe” would be considered unauthorized and non-compliant.

OSG responded that it was producing a different recipe after it developed internal concerns about the availability and quality of M-ATV compliant raw materials. The M-ATV is a vehicle developed by the Oshkosh Corporation for the MRAP program. OSG argued that after performing tests on its own “recipe” it found that its already-delivered, out-of-spec products produced out of compliance with the contracts “did not affect performance” and that it had even submitted its own recipe to the Army as a SAR for future sales.

The US Army was placed under enormous pressure by OSG’s actions. Some of OSG’s products had already been installed on vehicles and any supply chain issues would delay its supply lines. The product was desperately needed. That much is known with certainty. What is not known is whether OSG rallied any friends within Congress, the Department of Defense, or elsewhere to cut a deal with the buyer. What is certain is that a sweetheart deal was indeed made.

On June 4, 2015 the US Army approved OSG’s new recipe, which relieved the pressing problem of the already received and installed transparent glass armor. The Army didn’t cancel any of OSG’s contracts. However, on June 24, 2015 it ordered that any future OSG deliveries would have to comply with the original US government owned “secret recipe” specified in the contract. It also ordered OSG to make cash and in-kind payments to cover additional government costs incurred for handling and processing “nonconforming goods previously delivered.” But it allowed OSG to extend deadlines on “all outstanding deliveries.”

OSG’s competitors were livid, and Schott even sued over the contract. But the litigant could not convince the presiding judge that there was any prejudice in the actual issuance of the contract. The legal standard for prejudice is establishing that if it had not been for a procurement process error, they could have won the contract. Since Schott was—unlike OSG—not low-balling and intending to manufacture and deliver non-compliant products, their prices were so high that the legal standard intended to prevent prejudicial awards could not protect them.

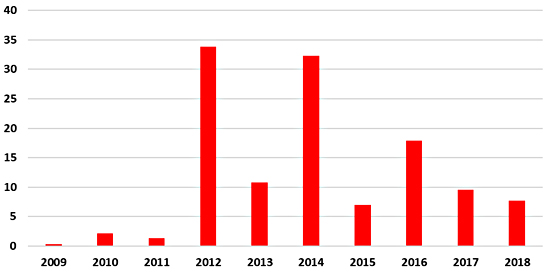

The fact that particular contracts are for MRAPs is a government secret. So, the five contracts cannot be identified from within publicly accessible listings of payments that have exact dollar amounts related to contracts awarded to OSG. However, military contract databases do reveal that in 2016, in an uncharacteristic move, OSG repaid the US government $4.7 million. It is not known if any American military personnel whose lives depended on non-compliant OSG armor, ever paid the ultimate price over Oran’s contracting malfeasance.

From the perspective of US taxpayers and residents of Greensville County in Virginia, there are a number of problems with the way OSG does business that are unique to its status as a recipient of massive amounts of funding orchestrated by the Virginia Israel Advisory Board. VIAB is presently the only taxpayer funded state government Israel export promotion council in the US Some VIAB board members hold equity stakes and positions as corporate officers in Israeli companies or joint ventures seeking to start operations in Virginia. Others are long-term officers of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) and other national Israel affinity and lobbying organizations.

Most news reports about Oran portray the opposite of reality. One year 2019 report, from the Area Development Online news organization ran the headline, “Oran Safety Glass Expands Greensville County, Virginia, Manufacturing Complex.” A far more accurate headline would have been, “Greensville County Expands Oran Safety Glass Complex.” Initially VIAB and Oran played every angle to squeeze millions in funding out of the state and county, all so Oran could be well-positioned to submit its fraudulent bids for US military contracts. Oran is now one of VIAB’s most cherished projects, and is prominently featured in its promotional materials, as mentioned in VIAB meeting minutes:

We are marketing ourselves in Israel, [and] created a brochure. Leveraging United Airlines direct flight[s]. Using mass media organizations. We are focused on doing a campaign geared to the Kibbutz industry. A lot of innovation in water and technology has come from that niche (i.e. Drip Irrigation and desalinization). We have one kibbutz business that came to Virginia, Oran Safety Glass in Emporia, currently employing 150 people. They sell their glass to the military and Caterpillar tractor, they sell back to Israel through foreign military funding, and to the civilian market. A tiny Kibbutz company has expanded exponentially. Sometimes it takes a known person that is trusted to guide these small companies to take interest in the US.

Leading mass media organizations do factor heavily in VIAB’s self-promotion. The Washington Post featured customers of Sun Tribe Solar as alternative energy leaders, without mentioning that the companies that own it do business in Israeli occupied territories. While the “known person” remains unknown,” VIAB brought along five major campaign contributors on former Governor Terry McAuliffe’s 2016 delegation to Israel. During the trip Virginia representatives signed a Memorandum Of Understanding (PDF) turning Virginia Tech into Sabra Dipping Company’s uncompensated US sales and marketing division while pledging additional funding to Israeli companies.

Oran’s state subsidies from Virginia were delivered in three phases. The first, they funded Oran startup operations in Virginia, and then two expansion phases as defense contracts were expected to pour in. In July of 2006, a performance agreement was executed between Oran, the Virginia Economic Development Partnership, the Tobacco Commission and Greensville County. The parties agreed that in exchange for government support OSG would make a $4.1 million capital investment to start production in Virginia and create 45 new jobs within 30 months.

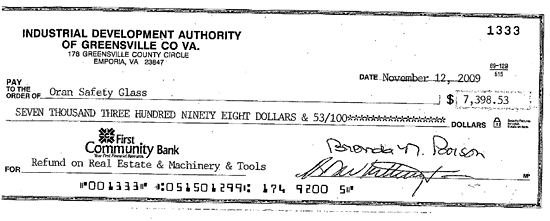

In 2007 the Greensville County Industrial Development Authority leased five and a third acres of land and an 82,800 square foot industrial building for ten years to OSG. The County obtained grants to perform a nearly $600,000 upgrade to the facility, including two separate Tobacco Commission grants in the amounts of $100,000 and $125,000, a $50,000 Emporia/Greensville Industrial Development Corporate grant, as well as $125,000 from the Governor’s Opportunity Fund. The project also applied for a Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development “Virginia Enterprise Zone Real Property Improvement Grant” of $125,000.

Greensville County even agreed to go into debt to bring in OSG by securing a loan for $400,000 from the Virginia Small Business Finance Authority to cover any “Phase I” cost shortfalls. There were cascading effects. Other entities such as the Mecklenburg Electric Cooperative also agreed to go into debt by up to $400,000 to build out infrastructure necessary to supply electricity to OSG. The county also waived water and sewer connection fees in the amount of $20,000 and $4,300 in building permitting fees. The government parties showered another quarter million in “job creation grants,” “training and recruitment incentive grants” and free classroom space for “pre-employment testing and training” to assist in the creation of a workforce for OSG. On December 17, 2017, the Greensville County Industrial Development Authority finally “sold” the manufacturing facility which it carried on its books as a $1,140,000 asset, to Oran Safety Glass for a price equivalent to the outstanding loan balance on the property, or $436,644.

Excluding military contracts, Oran is known to have received close to $3 million in government economic development subsidies. In return, Oran was supposed to provide jobs with solid pay and a boost to tax revenues, but there is no independent evidence that it is meeting any of its performance benchmarks. An examination of records released by Greensville County under the Virginia Freedom of Information Act reveals the county has only once attempted to claw back funds over non-performance and has little incentive to or capability to probe too deeply. However, with Oran’s military contracts in steep decline, local stakeholders could soon begin to press Oran’s government subsidizers to respond as to whether Oran has jeopardized the county’s financial viability.

Perhaps the issue of greatest concern to Virginians, other Americans and the rest of the world are the incentives created by OSG and other Israeli military contractors VIAB is herding into Virginia. Ever more military conflict in the Middle East is good for them. Less conflict is bad. With military contracts at Oran in seeming eclipse, the likely result of Pentagon mistrust of Oran’s past contracting practices, there is new pressure on VIAB, their fellow operatives at AIPAC and the wider Israel affinity ecosystem that supports Israeli military contractors, and the government of Israel to do something. Israel clearly has the ability to create new demand for weapons production that even top-tier US military contractors like Boeing and Lockheed Martin do not. What could be better than for the US to respond to additional Israeli demands for on-the-ground military action against Israel’s rivals? Or sending more heavy armor into Syria? Or launching new armored ground campaigns against Iran or even inside Iraq that benefit Israel, Oran Safety Glass, and the new horde of other Israeli military contractors streaming into Virginia under VIAB’s guidance?

Grant F. Smith is the director of theInstitute for Research: Middle Eastern Policy in Washington and the author of the new book, The Israel Lobby Enters State Government: Rise of the Virginia Israel Advisory Board, available in paperback and audio book. IRmep is co-sponsor of the annual Transcending the Israel Lobby at Home and Abroad conference at the National Press Club.